“sumptuary”

― Elizabeth Fremantle, Queen's Gambit Free 1st Chapter

The earliest sumptuary regulations in Christian Europe were

church regulations of clergy, distinguishing what ranks could wear which items

of vestments or (to a lesser extent) normal clothes on particular occasions;

these were already very detailed by 1200, in early recessions of canon law. Next followed regulations, again flowing

from the church (by far the largest bureaucracy in Medieval Europe), attempting

to enforce the wearing of distinctive clothing or badges so that members of

various groups could be readily identified, as branded criminals already could

be.

The groups covered included Jews, Muslims, heretics such as

Cathars (repentant ones were made to wear the Cathar yellow cross), lepers and

sufferers from some other medical conditions, and prostitutes. The enactment

and effectiveness of such measures was highly variable — efforts to make lepers

wear long whitish robes were apparently not successful, as they are usually

shown in pictures wearing normal clothes, but carrying a horn or rattle to warn

others of their approach.

Sumptuary laws issued by secular authorities aimed at

keeping the main population dressed according to their "station" do

not begin until the later 13th century.

These laws were addressed to the entire social body, but the brunt of

regulation was directed at women and the middle classes. Their curbing of

display was ordinarily couched in religious and moralizing vocabulary, yet was

affected by social and economic considerations aimed at preventing ruinous expenses

among the wealthy classes and the drain of capital reserves to foreign suppliers.

Non-Christians'

clothing

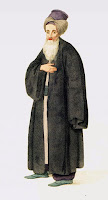

The efforts to make Jews and Muslims dress distinctively

date from 1215 or shortly before. One aspect of medieval sumptuary laws was to

make the Jewish and other non-Christian populations identifiable by the wearing

of special yellow badges or the conical Jewish hat, the latter having initially

been a voluntary form of distinctive dress imported from the Islamic world. Canon 68 of the Fourth Council of the

Lateran in 1215 stipulated that Jews and Muslims should wear distinctive

clothing; avoiding sexual contact between the populations was the reason given.

The Jews of Castile, the largest population in Europe, were

exempted by the pope Judenhut or a yellow badge in the form of a wheel or ring

(the "rota"), or, in England, a shape representing the Tablets of the

Law. Muslims usually were supposed to wear a crescent-shaped patch or Eastern

dress. Enforcement of these laws seems to have dwindled gradually, and the hat

is not often seen in pictures after the 15th century, although the ring

continues after that.

The Jews of Castile, the largest population in Europe, were

exempted by the pope Judenhut or a yellow badge in the form of a wheel or ring

(the "rota"), or, in England, a shape representing the Tablets of the

Law. Muslims usually were supposed to wear a crescent-shaped patch or Eastern

dress. Enforcement of these laws seems to have dwindled gradually, and the hat

is not often seen in pictures after the 15th century, although the ring

continues after that.

Courtesans

Special forms of dress for prostitutes and courtesans were

first introduced in Ancient Rome in the form of a flame-colored toga and

re-introduced in the 13th century: in Marseilles a striped cloak, in England a

striped hood, and so on. Over time, these tended to be reduced to distinctive

bands of fabric attached to the arm or shoulder, or tassels on the arm. Later

restrictions specified various forms of finery that were forbidden, although

there was also sometimes a recognition that finery represented working

equipment (and capital) for a prostitute, and they could be exempted from laws

applying to other non-noble women. By the 15th century, no compulsory clothing

seems to have been imposed on prostitutes in Florence, Venice (the European

capital of courtesans) or Paris.

England

In England, which in this respect was typical of Europe,

from the reign of Edward III in the Middle Ages until well into the 17th

century, sumptuary laws dictated what color and type of clothing, furs,

fabrics, and trims were allowed to persons of various ranks or incomes. In the

case of clothing, this was intended, amongst other reasons, to reduce spending

on foreign textiles and to ensure that people did not dress "above their

station.”

Elizabethan Sumptuary Laws

In Greenwich on 15 June 1574 Queen Elizabeth I enforced some

new Sumptuary Laws called the 'Statutes of Apparel'. The reasons were to limit

the expenditure of people on clothes - and of course to maintain the social

structure of the Elizabethan Class system.

Statutes of Apparel

The excess of apparel and the superfluity of unnecessary foreign wares thereto belonging now of late years is grown by sufferance to such an extremity that the manifest decay of the whole realm generally is like to follow (by bringing into the realm such superfluities of silks, cloths of gold, silver, and other most vain devices of so great cost for the quantity thereof as of necessity the moneys and treasure of the realm is and must be yearly conveyed out of the same to answer the said excess) but also particularly the wasting and undoing of a great number of young gentlemen, otherwise serviceable, and others seeking by show of apparel to be esteemed as gentlemen, who, allured by the vain show of those things, do not only consume themselves, their goods, and lands which their parents left unto them, but also run into such debts and shifts as they cannot live out of danger of laws without attempting unlawful acts, whereby they are not any ways serviceable to their country as otherwise they might be

—Statute issued at Greenwich, 15 June 1574, by order of Elizabeth I

.jpg)